Light Pollution and Environmental Justice

Review of: Nadybal, S. M., Collins, T. W., & Grineski, S. E. (2020). Light pollution inequities in the continental United States: A distributive environmental justice analysis. Environmental Research, 189, 109959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109959

On September 15, 1982, Dollie Burwell dropped her 10-year-old daughter Kim off at the bus stop, went home, and prepared to be arrested. That morning, 125 people were gathering at the Coley Springs Baptist Church in Afton, NC, steeling themselves to walk the mile and a half to the sight of a hazardous waste landfill where 60 police officers dressed in full riot gear were waiting for them. As she was preparing to leave her house, she turned and saw Kim standing at the door. “I want to come with you”

Dollie hesitated, then, told her daughter the truth. “I’m going to be arrested today.”

But Kim persisted, “The other people will take care of me and I know how to call daddy and my aunt”

Dollie didn’t have time to argue, so she relented.

Bettman/Getty Images Source

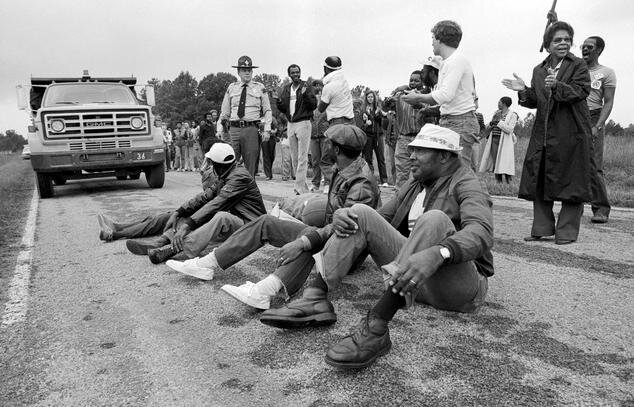

At the protest, activists were marching with signs. Neighbors were chanting and singing. Some were lying in the path of several large trucks that were delivering contaminated soil to the site. As the police cleared the protesters and the trucks began to move, Reverand Jarboe, a local minister, defiantly jumped into the road and was hit by one of the trucks. His injuries were minor but the act reminded participants that the line between a peaceful protest, civil disobedience, and chaos was thin. In the confusion, Dollie became separated from her daughter and, as planned, was arrested. As she was led away, Dollie spotted Kim being interviewed by Dan Rather and a host of other reporters. That night her interview aired on the CBS Evening News. To Dollie’s surprise, her daughter was also arrested. Later, Kim recalled the experience.

“I walked to the landfill in the front with my mom. And when havoc started, we got separated. And I was just screaming, ‘Don’t bring the trucks in. I don't want to die from cancer.’ And they picked me up, and they picked my mom up and at that point in time I was still screaming. I was the only child actually on the adult paddy wagon to go to jail that day.”

Photo: Ricky Stilley Source

Four years earlier, on June 24, 1978, Robert J. Burns, pulled into the yard at the Ward Transformer Company in Raleigh, near the intersection of what is now I-540 and Glennwood Ave. There, he carefully filled his tanker truck with 750 gallons of oil laced with highly toxic PCBs. The vehicle was outfitted with piping connected to a nozzle extending out the back of the passenger side of the truck which could be opened while the truck was moving. Under the cover of darkness, he drove south. When he reached the Fort Bragg Military Reservation, Burns opened the valve and unleashed a steady stream of toxic, cancer-causing PCBs along the roads on the base. When the tank was empty, he returned for another load. Throughout July and the first few weeks of August, Burns, with the help of his two sons Randall and Timothy, dumped PCB oil along rural roads from Fort Bragg to the Virginia state line. To avoid detection, Burns and his sons selected secluded stretches of road. They left the valve open except when they passed through inhabited or well-lit areas. In less than two months, the Burns family contaminated more than 200 miles of roadway throughout eastern North Carolina. By the end of July, residents in the area began to notice strips of oily discolored soil and dead vegetation along the small local roads where they often walked and their children played.

As summer turned to fall, state investigators got involved and quickly focused their attention on Burns and Robert Earl Ward, owner of Ward Transformer Company. As investigators closed in, Robert Burns confessed to the dumping and was arrested. He was sentenced to 3 to 5 years in a North Carolina prison. A few months later in January 1979, Ward was indicted by a federal grand jury on eight counts of knowingly and willfully causing PCBs to be disposed of in North Carolina, and for aiding and abetting Burns in the crime. On May 22, 1981, Ward was convicted on all eight counts and served nine months at a federal penitentiary.

Beginning in September 1982, the State of North Carolina began scraping up strips of contaminated soil three inches deep and 30 inches wide, placing it in waiting dump trucks six tons at a time. The destination for the 10,000 truckloads of toxic debris was a newly constructed landfill in Afton, the heart of Warren County. When Burwell and her neighbors heard of the plan, they started to organize. After an exhaustive legal fight to stop the landfill failed, they turned to the time-honored tradition of protest and non-violent civil disobedience. The spill and the state’s decision to dispose of the contaminated soil in Afton, kicked off the environmental justice movement in the United States, as the issue united for the first time environmental and racial justice activists. As Reverend Jarboe stated before he jumped in front of the truck, ''I know what's right. This is a life-and-death issue.''

In 1980, the population of Warren County was estimated to be 16,232. Sixty percent of those residents were Black (the state-wide percentage was 22%). Warren County also ranked 97th of 100 counties in per capita income with most residents subsisting on about two-thirds of the income of the rest of the state. Residents were convinced that Afton was chosen for the landfill because most of the residents in Warren County were poor and Black. Dollie Burwell described it this way,

“One of the things we recognized even before the dumping of the PCBs in Warren County was that Blacks had no political power…. So, when people realized that a political decision by the Governor was made to bury PCBs in Warren County, people could see that, if in Warren County we were more actively involved politically, we would have more clout…. Not only was Warren County predominantly Black and predominantly poor, but it was politically impotent. And that was just the recipe for dumping.”

After six weeks of protest and more than 500 arrests, 60,000 tons of waste were eventually dumped at the site. Although they failed to stop construction of the landfill, the Warren County protests had a lasting influence and prompted a number of studies to measure the connection between race and hazardous waste. A Government Accounting Office study, released in 1983, found that three out of four hazardous waste landfills in the southern U.S. were located in communities where African Americans made up at least twenty-six percent of the population and per capita incomes were significantly below state averages. In 1987, another study by the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice found that three out of five Black and Hispanic Americans lived in a community that housed an “uncontrolled toxic waste site,” a closed or abandoned site that posed a threat to human health and the environment. The study also found that race was the strongest variable in predicting the location of toxic waste facilities.

Photo: BET.com

The legacy of Warren County is still with us today. Environmental injustice remains an important and unresolved issue in the U.S. Despite some progress, minority and low-income communities continue to disproportionally suffer from poor environmental conditions. In recent years, it has been confirmed that minority and low-income populations are exposed to greater levels of noise, air pollution, and toxic chemicals. Their drinking water is more likely to be contaminated, and their neighborhoods have less access to parks and open space. Recently, studies have also shown that these communities bear the brunt of yet another form of pollution with known impacts on human health and well-being: light pollution.

In April of 2020, scientists from the University of Utah published the results of a study that “empirically documented a pattern whereby neighborhoods with higher proportions of Black, Hispanic, and Asian residents and renter-occupants were exposed to greater ambient light at night….”

Exposure to light can have direct and indirect effects on human health. The retinas in our eyes contain a type of cell called intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Stimulation of these cells influences our circadian rhythm primarily by suppressing the production of melatonin, which in turn disrupts normal sleep patterns and negatively affects cognitive performance, mood, memory, and other physiological functions. Sleep disorders associated with reduced melatonin levels are a contributing factor in depression, anxiety, and obesity which can increase the risk of diabetes, gastrointestinal ailments, heart attacks and strokes. Artificial light is also associated with an increased risk of prostate and breast cancers in some populations.

Nadybal and her colleagues used the New World Atlas of Artificial Sky Brightness (NWAASB) to assess light pollution levels for more than 70,000 census tracts across the continental United States. Data on racial and ethnic composition and socio-economic conditions for each tract were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau. The percentages of rental units and median household income were used as proxies for socio-economic status. The analysis determined the average exposure to light pollution for each of the racial categories included in the census data. The levels are presented as luminance values with the unit “microcandela per square meter” (mcd/m2), which simply measures the amount of light that falls on each square meter of land. The study found that exposure levels for Asians, Hispanics, Blacks, and Pacific Islanders respectively were 106.7%, 99.4%, 98.5%, and 53.1% higher than those for Whites. With respect to renter-occupancy, each 22% increase in the percentage of renter-occupied homes was associated with a 39% increase in the light pollution.[1]

The efforts of the warren county residents and other environmental justice activists eventually led to political action. In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 12898 that directs federal agencies to:

“identify and address the disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of their actions on minority and low-income populations, to the greatest extent practicable and permitted by law.”

To comply with this order, federal agencies typically address environmental justice concerns when completing environmental impact assessments to determine if minority and low- income communities would be disproportionately exposed to health and environmental impacts. To date, very few environmental justice studies have addressed potential impacts from light pollution. Nadybal’s study suggests that the effects of increased exposure to artificial light should always be considered in these analyses.

Since the 1980s, local, state, and federal governments have made significant strides in addressing and preventing disproportional environmental impacts to disadvantaged communities. Dollie and Kim Burwell and countless other activists were willing to risk their safety and their freedom to raise awareness of the issue. However, as this and other studies illustrate, much work remains to be done. We now know that minority and low-income populations are at increased risk of numerous health issues from light pollution, and these impacts must be addressed. Fortunately, this problem is easy to fix. Following the Five Principles for Responsible Outdoor Lighting (https://www.darksky.org/our-work/lighting/lighting-principles/) is not technically challenging or expensive. It just requires a basic understanding of the issue, personal responsibility, and political will. Following these simple strategies will help us achieve what the protesters in Warren County desperately wanted nearly 40 years ago – environmental justice.

[1] The relationship between income and light levels was less direct with low-income and high-income neighborhoods associated with less light pollution compared to those with medium income levels.