Curiosity and the Hidden Costs of Light Pollution

“The true sign of intelligence is not knowledge but imagination. I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.”

--Albert Einstein[1]

On a cool evening in the fall of 1938 just outside of Washington, DC, 10 year old Vera Rubin lies in her bed looking up at the stars through an open window. Facing north, her window frames the constellations of Cassiopeia, Cepheus, and Ursa Minor. She is obsessed with the night sky and reads everything she can find on astronomy. But it is that sky full of stars that captures her imagination.

Vera Rubin at Work, NOIRLab, By KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA - CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=128906237

“By about age 12, I would prefer to stay up and watch the stars than go to sleep. I started learning. I started going to the library and reading. But it was initially just watching the stars from my bedroom…. There was just nothing as interesting in my life as watching the stars every night…It really was watching the stars. It was getting some sense of the motion of the earth. I found it a remarkable thing. You could tell time by the stars. I could see meteorites.…when there were meteor showers and things [like that], I would not put the light on. Throughout the night, I would memorize where each one went so that in the morning I could make a map of all their trails. I read a lot of books…. But I was already hooked.”[2]

To support this obsession, her father helps her build a telescope, “…which was really a total flop, but was sort of fun. I ordered a lens from Edmund's and got a cardboard tube that linoleum came rolled on. I tried to take some pictures, but none of it worked because the telescope didn't track.”[3] By high school, she knows she wants to be an astronomer. Overcoming a host of obstacles as a women in a male-dominated field, Vera went on to become a distinguished scientist whose work provided convincing evidence for the existence of dark matter.

At about the same time that Vera is gazing at the stars through her bedroom window, Victor Blanco, a teenager in Puerto Rico is tending the pigs on his family farm. Like Vera, he is captivated by the night sky and names his pigs after astronomical objects - Ceres, Vesta, Ganymede. Also like Vera, he reads incessantly and builds a telescope to help explore his passion for the stars. Fortunately, his attempt was a bit more successful than Vera’s.

“…I also became an avid reader of popular science magazines, one of which featured how-to-do-it projects for young readers, including making a reflecting telescope. I obtained the glass blanks, Carborundum, and rouge to make a 6-inch telescope that competed for the space where I raised my astronomically named pigs. The reflector luckily produced excellent images.[4]”

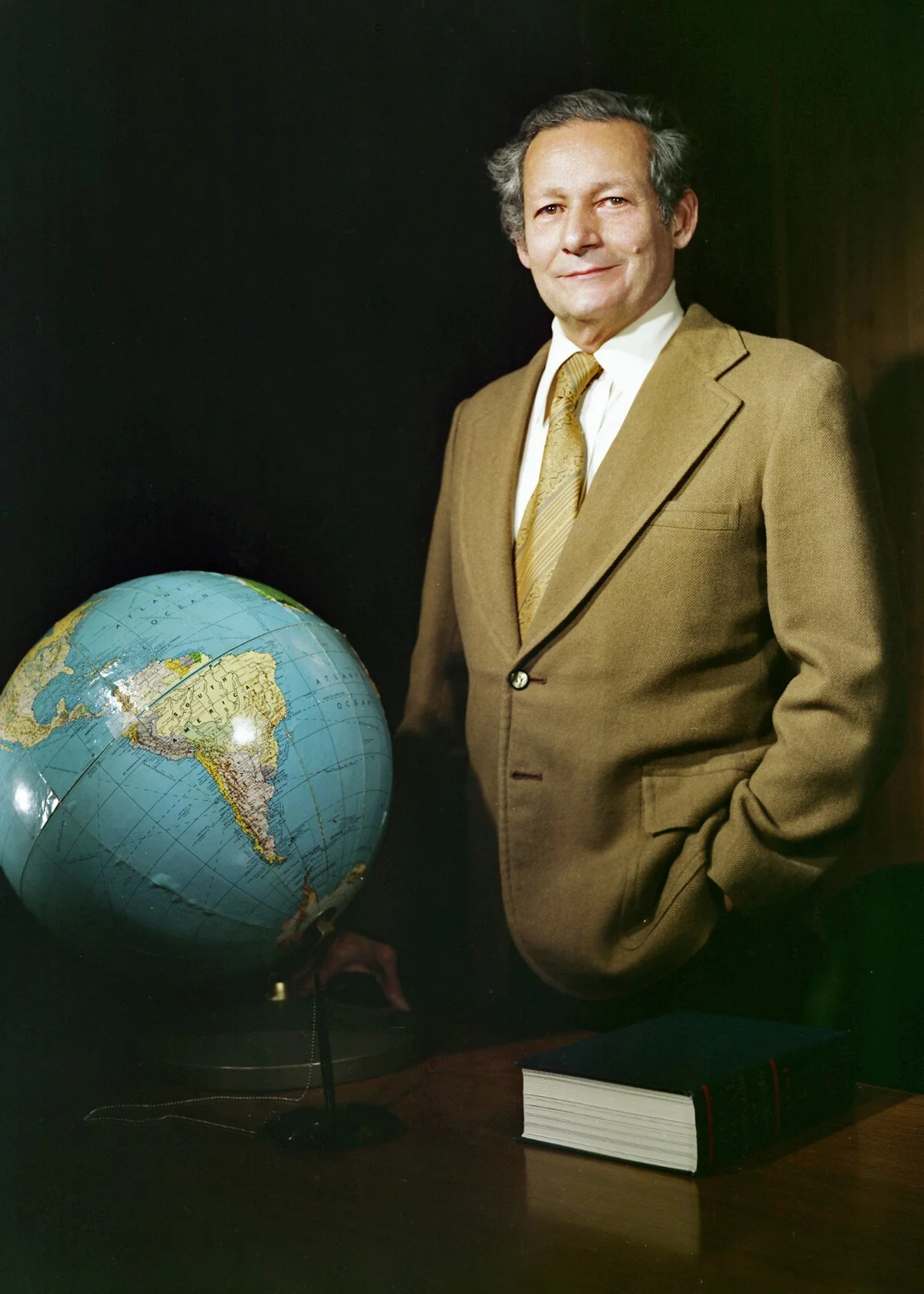

Victor Blanco By NOIRLab/NSF/AURA, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Even though childhood dreams of studying the cosmos are not generally considered prudent or realistic in Puerto Rico at the time, the fire is lit and after a brief period studying medicine, Victor switches to astronomy. He quickly becomes a prominent astronomer conducting pioneering research focusing on the stars in the central region of our galaxy and the small and large Magellanic Clouds.

Both Vera and Victor credit their ability to view the night sky during their childhood and the curiosity generated by that experience as primary motivation for their interest in astronomy and their ultimate choice of a career. They both demonstrated a strong emotional connection to the view of the cosmos from their childhood homes. They both read incessantly but it was the practice of staring up into the dark sky that captivated their imagination. As Vera put it, “It really came from the sky. In the late 1930's, I remember, there was an alignment of five planets. That impressed me...Then there were several auroral displays. It was those things that really [captured my interest]. It was the visual experience more than what I read in books.[5]”

The term “noctcaelador” was coined by psychologist William Kelly to describe a strong "emotional attachment to, or adoration of, the night sky". In a previous post, I discussed the positive social and emotional changes that we encounter when we experience awe while viewing a star filled sky. Similarly, studies of noctcaelador have suggested that an emotional connection to the night sky is associated with a plethora of positive characteristics including openness to experience, an attraction to investigative and artistic pursuits, sensation-seeking, a rational, cognitive approach to problem solving, a tendency to become deeply involved and attentive to subjects of interest, and a willingness to consider unusual ideas and possibilities[6] – perfect qualities for a career in science.

Radio telescope at the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) Photo: Frank Turina

Another quality that has been associated with noctcaelador is curiosity. In psychological research, curiosity is generally defined as a desire for new knowledge or experience often aroused by objects and ideas that are complex or ambiguous. What could be more complex and ambiguous than the stars, planets, galaxies, and other objects we see when we look deeply into the night sky and the feelings we encounter when contemplate our place in the universe?[7]

“Holy curiosity[8],” as Einstein described it, has deep biological origins and provides us with evolutionary advantages. The primary evolutionary benefit of curiosity is to encourage living things to explore their world in ways that help them survive. For any organism, exploring an environment can help it to uncover new resources, potentially giving it a leg up against competitors or predators[9].

However, curiosity in humans is unique in the animal kingdom. Dr. Jacqueline Gottlieb a neuroscientist at Columbia University recently used brain imaging to determine what happens to our brain when we experience curiosity[10]. To her, “what distinguishes human curiosity is that it drives us to explore much more broadly than other animals, and often just because we want to find things out, not because we are seeking a material reward or survival benefit. This leads to a lot of our creativity.” Studies have also shown that gaining information and answering questions that puzzle us is deeply satisfying. Curiosity is tied to the dopamine system, so we get a dose of feel-good chemicals whenever we satiate our curiosity.[11]

Recent research also suggests what Vera Rubin and Victor Blanco clearly knew, that curiosity is sparked by views of the night sky. A study by William Kelly and Don Daughtry demonstrated that people who are emotionally attached to the night sky tend to score high on measures of curiosity. They note that both concepts are related to several personality traits including an openness to experience and a need for understanding. However, due to the old adage that correlation does not equal causation, we can’t be sure whether experiencing the night sky sparks curiosity or whether curious people are more likely to look up at the stars. However, the relationship is strong and holds up even when controlling for other key variables. [12]

I witnessed this connection first hand on a recent trip to Chile. On an unseasonable warm day in August, we loaded into a van in the beautiful seaside town of La Serena. We were headed to a remote outpost high in the Andes mountains to get an up close, behind the scenes tour of some of the most sophisticated telescopes in the world. We were travelling as the newest members of the Astronomy in Chile Educational Ambassadors (ACEAP) program. The Program brings amateur astronomers, planetarium personnel, and science educators to US astronomy facilities in Chile.

The first stop on our tour was Cerro Pachon. The site, which sits at an elevation of just under 9,000 feet above sea level, is home to the 8.1 m Gemini South and the 4.1 m Southern Astrophysical Research (SOAR) telescopes. Gemini South along with its twin observatory on Mauna Kea can explore the entire northern and southern skies in optical and infrared light. Images obtained from these instruments are among the sharpest ever obtained by a ground-based telescope, roughly the equivalent of being able to detect the separation between a set of headlights from a distance of 2,000 miles. [13]

All- sky view of the Milky Way from the Atacama Dessert, Chile Photo: Frank Turina

The SOAR Telescope is among the foremost research facilities available to astronomers in the southern hemisphere, producing high quality images at wavelengths from optical to near-infrared. One of the unique features of the SOAR facility over traditional telescopes is that it holds multiple sensors and cameras. In minutes, astronomers can change from one instrument to another by just rotating a single mirror inside the telescope. Prior to this innovation, only one instrument could be mounted on a telescope at a time, and a change of instruments was laborious and time consuming. [14]

A few hundred yards to the southwest of SOAR, sits another new telescope. It is so new that at the time of our visit, it was still under construction. The observatory will house a wide-field reflecting telescope with an 8.4-meter primary mirror that will photograph the entire visible sky every few nights. Images will be recorded by a 3.2-gigapixel CCD camera, the largest digital camera ever constructed. The name of this facility is the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, after the little girl, consumed by curiosity, staring at the night sky from her bedroom in Washington.

About 10 miles away, on a mountain adjacent to Cerro Pachon sits the observatories of Cerro Tololo. The centerpiece of Cerro Tololo is a 4-meter telescope dedicated in 1995. The telescope is designed to help scientists better understand the expansion of the universe and is most famous for its use in the Nobel Prize winning discovery of dark energy in 1998. This telescope is named after Victor Blanco, the Puerto Rican farmer who named his livestock after astronomical objects and explored the solar system with a home-made telescope. It is fitting that two of the most sophisticated telescopes on the planet, designed for the sole purpose of satisfying our questions about the stars, are named after a pair of astronomers who followed their childhood curiosity into distinguished careers as astronomers.

These instruments were built solely to answer questions about the cosmos that have intrigued us since the fist humans gazed at the stars and wondered. To help us understand the nature of the tiny specks of light we see in the night sky. To this day, this insatiable need to explore our universe drives advancement of astronomy. Albert Einstein understood the importance of curiosity in scientific pursuits, stating:

"The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing. One cannot help but be in awe when he contemplates the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvelous structure of reality. It is enough if one tries merely to comprehend a little of this mystery every day."[15]

Noctcaelador, that deep emotional connection to the cosmos, germinates an insatiable need to understand its nature. When views are marred by light pollution, opportunities to develop this connection are limited. In a recent article appearing in Nature Scientific Reports, William Kelly and Dan Daugherty explore the relationships between light pollution and curiosity about the night sky. Their results show that, among populations with low light pollution, a feeling of “wonder about the universe” is prevalent. The authors conclude that:

”Low light pollution is linked with the tendency of the population to feel wonder about the universe and to become interested in exploring it….The opportunity to see the stars in the night sky could engender interest in astronomy and greater chances of gaining practice in everyday scientific thinking. Indeed, many astronomers report that, in their youth, seeing the night sky triggered a feeling of “wonder” about the universe, and that this was a motivator for them aspiring to become a scientist.”[16]

Unfortunately, the views that ignited the curiosity in Vera Rubin, Victor Blanco, and countless other scientists are disappearing. Rubin noted that in the early 1940s, even in the midst of Washington, DC, you could see the stars. Today, this is no longer possible. More than 80 percent of the US population can’t see the Milky Way from their homes. They are being robbed of that fundamental source of inspiration and curiosity. For me, this is a significant and often overlooked cost of light pollution

For millennia the night sky was an engine that sparked curiosity. It made people want to go to the moon, it inspired people to build telescopes, to paint, to compose music, to write classic literature, to wonder where we came from and search for answers. In the last century, that fountain of curiosity has been cloaked by a fog of artificial light. But it’s not gone. The inspiration for the observatories I toured in Chile is still above us. We just need to recognize its value and understand the power of the night sky to generate questions and to motivate us to seek answers. So turn out the lights, look up, and be curious.

Sources

[1] Albert Einstein Letter to Carl Seelig (11 Mar 1952), Einstein Archive 39-013 Retrieved from https://wist.info/topic/curiosity/

[2] Interview of Vera Rubin by Alan Lightman on 1989 April 3, Niels Bohr Library & Archives, American Institute of Physics, College Park, MD USA, www.aip.org/history-programs/niels-bohr-library/oral-histories/33963

[3] Ibid

[4] Blanco, V. M. (2001). Telescopes, Red Stars, and Chilean Skies. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 39(Volume 39, 2001), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.astro.39.1.1

[5] Interview of Vera Rubin

[6] Development and testing of the Night Sky Connectedness Index (NSCI). (2024). Journal of Environmental Psychology, 93, 102198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102198

[7] Kidd C, Hayden BY. The Psychology and Neuroscience of Curiosity. Neuron. 2015 Nov 4;88(3):449-60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.010. PMID: 26539887; PMCID: PMC4635443.

[8] Retrieved from The Center for History of Physics, American Institute of Physics https://history.aip.org/exhibits/einstein/ae77.htm

[9] Brain-Imaging Study Reveals Curiosity as it Emerges | Columbia | Zuckerman Institute. (n.d.). Retrieved November 20, 2024, from https://zuckermaninstitute.columbia.edu/brain-imaging-study-reveals-curiosity-it-emerges

[10] Ibid

[11] Kidd C, Hayden BY. The Psychology and Neuroscience of Curiosity. Neuron. 2015 Nov 4;88(3):449-60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.010. PMID: 26539887; PMCID: PMC4635443.

[12] Kelly, W. E., & Daughtry, D. (2016). The Case of Curiosity and the Night Sky: Relationship between Noctcaelador and Three Forms of Curiosity. Education, 137(2), 204–208.

[13] About—History—Gemini Telescopes, Nifty 50 | NSF - National Science Foundation. (n.d.). Retrieved November 20, 2024, from https://www.nsf.gov/about/history/nifty50/geminiscopes.jsp

[14] Hub, M. (2016, December 15). SOAR’s Chapel Hill Origins. UNC Media Hub. https://mediahub.unc.edu/soar/

[15] From the memoirs of William Miller, an editor, quoted in Life magazine, May 2, 1955; Expanded, p. 281 Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/einstein/wisd-nf.html#:~:text=%22The%20important%20thing%20is%20not,of%20this%20mystery%20every%20day.%22

[16] Barragan, R. C., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2024). Opportunity to view the starry night sky is linked to human emotion and behavioral interest in astronomy. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 19314. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69920-4